U.S. flag raised on Iwo Jima on February 23, 1945

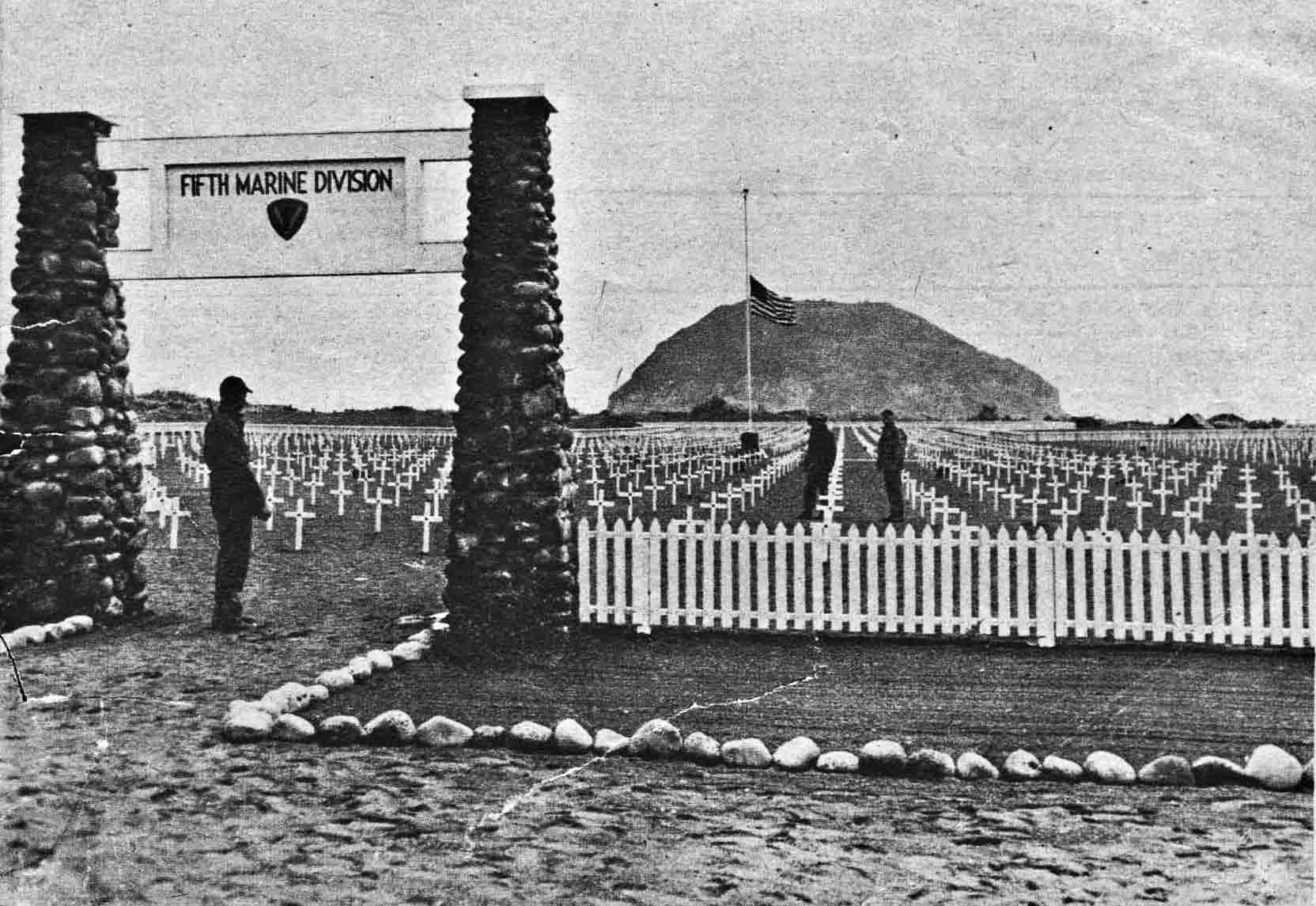

U.S. flag raised on Iwo Jima: During the bloody Battle for Iwo Jima, U.S. Marines from the 3rd Platoon, E Company, 2nd Battalion, 28th Regiment of the 5th Division take the crest of Mount Suribachi, the island’s highest peak and most strategic position, and raise the U.S. flag.

Marine photographer Louis Lowery was with them and recorded the event. Americans fighting for control of Suribachi’s slopes cheered the raising of the flag, and several hours later more Marines headed up to the crest with a larger flag.

Joe Rosenthal, a photographer with the Associated Press, met them along the way and recorded the raising of the second flag along with a Marine still photographer and a motion-picture cameraman.

Rosenthal took three photographs atop Suribachi. The first, which showed five Marines and one Navy corpsman struggling to hoist the heavy flag pole, became the most reproduced photograph in history and won him a Pulitzer Prize. The accompanying motion-picture footage attests to the fact that the picture was not posed.

Of the other two photos, the second was similar to the first but less affecting, and the third was a group picture of 18 Marines smiling and waving for the camera. Many of these men, including three of the Marines seen raising the flag in the famous Rosenthal photo, were killed before the conclusion of the Battle for Iwo Jima in late March.

In early 1945, U.S. military command sought to gain control of the island of Iwo Jima in advance of the projected aerial campaign against the Japanese home islands.

Iwo Jima, a tiny volcanic island located in the Pacific about 700 miles southeast of Japan, was to be a base for fighter aircraft and an emergency-landing site for bombers.

On February 19, 1945, after three days of heavy naval and aerial bombardment, the first wave of U.S. Marines stormed onto Iwo Jima’s inhospitable shores.

The Japanese garrison on the island numbered 22,000 heavily entrenched men. Their commander, General Tadamichi Kuribayashi, had been expecting an Allied invasion for months and used the time wisely to construct an intricate and deadly system of underground tunnels, fortifications, and artillery that withstood the initial Allied bombardment.

By the evening of the first day, despite incessant mortar fire, 30,000 U.S. Marines commanded by General Holland Smith managed to establish a solid beachhead.

During the next few days, the Marines advanced inch by inch under heavy fire from Japanese artillery and suffered suicidal charges from the Japanese infantry. Many of the Japanese defenders were never seen and remained underground manning artillery until they were blown apart by a grenade or rocket, or incinerated by a flame thrower.

While Japanese kamikaze flyers slammed into the Allied naval fleet around Iwo Jima, the Marines on the island continued their bloody advance across the island, responding to Kuribayashi’s lethal defenses with remarkable endurance.

On February 23, the crest of 550-foot Mount Suribachi was taken, and the next day the slopes of the extinct volcano were secured.

By March 3, U.S. forces controlled all three airfields on the island, and on March 26 the last Japanese defenders on Iwo Jima were wiped out. Only 200 of the original 22,000 Japanese defenders were captured alive.

More than 6,000 Americans died taking Iwo Jima, and some 17,000 were wounded.

How U.S. Marines Won the Battle of Iwo Jima

A look back at one of the most hard-fought battles of World War II

By the time they splashed their way onto its southeastern beach on February 19, 1945, many of the U.S. Marine invasion force wondered if there were any Japanese left alive on Iwo Jima. Allied aircraft, battleships and cruisers had spent the previous two and a half months pulverizing the volcanic outcropping with thousands of tons of high explosives, leaving it a smoldering heap of charred boulders and burned-out vegetation. A haze of smoke now covered much of the island, and the stench of cordite and sulphur hung heavy in the air. “There wasn’t a tree left standing”, Corporal Stacy Looney later remembered, “wasn’t anything left standing.”

The Marines had been told to expect heavy resistance, but the first waves of landing craft encountered only a few artillery bursts and scattered small arms fire. Thousands of infantrymen, tanks and vehicles were able hit the beach with relative ease. “There’s something screwy”, one corporal said of the ominous calm. The Marines were right to be suspicious. As soon as the first units advanced onto an ash-covered terrace beyond the shore, dozens of camouflaged Japanese batteries erupted with murderous mortar and machine gun fire, and artillery shells began raining down on the men and equipment still clogging the beach. “The honeymoon is over!” one officer yelled. In an instant, any illusions the Marines had of taking the island without a fight had evaporated.

Outside of its proximity to Japan—still some 750 miles away—the 8 square mile hunk of land at Iwo Jima carried little significance. It lacked adequate supplies of fresh water and other resources, and its shores were too rocky to act as harbors for Navy ships. But as World War II moved closer to its conclusion, the island had become a crucial steppingstone in the American push toward the Japanese homeland. B-29 Superfortresses had begun making bombing runs over Tokyo, and they needed Iwo Jima as an emergency landing site and staging ground for their fighter escorts. To seize the island, the U.S. high command had marshaled the 3rd, 4th and 5th Marine divisions of the V Amphibious Corps under Lt. General Holland “Howlin’ Mad” Smith. The total force included a staggering 70,000 men - the most Marines ever assembled for a single operation.

Standing in the way of the American invasion were some 22,000 Japanese led by General Tadamichi Kuribayashi. Under his leadership, Iwo Jima’s garrison had transformed the island into a labyrinth of natural caves, subterranean tunnels and fortified pillboxes and bombproofs. Nearly all of the Japanese emplacements contained a copy of a special order from Kuribayashi commanding his men to fight to the bitter end. “Above all, we shall dedicate ourselves and our entire strength to the defense of this island”, the instructions read. “Each man will make it his duty to kill ten of the enemy before dying.” Thanks to their stout defenses, Kuribayashi’s men had suffered surprisingly few casualties during the American artillery onslaught. When the Marines finally moved past the beach on the morning of February 19, they sat waiting with guns trained.

Once the shooting started, the American landing zone turned into a cauldron of shell bursts and mortar fire. Thomas McPhatter, one of several hundred African-American Marines who joined in the attack as amphibious truck drivers and ammunition handlers, later described the hellish scene to the Guardian.

“I jumped in a foxhole and there was a young white Marine holding his family pictures”, he said.

“He had been hit by shrapnel, he was bleeding from the ears, nose and mouth. It frightened me. The only thing I could do was lie there and repeat the Lord’s prayer, over and over and over.”

After braving the intense fire, U.S. troops established a beachhead and began knocking out Japanese pillboxes and trenches near the shoreline. Others made a stubborn slog through foot-deep volcanic ash and crossed to the island’s western side, cutting off its 550-foot-tall southern peak at Mt. Suribachi. By nightfall, more than 30,000 Marines had landed on Iwo Jima.

U.S. forces continued their advance over the next several days, capturing the first of three airfields and moving toward the island’s rock-strewn northern sector. On February 23, elements of the 28th Marines took the heights at Suribachi to the sound of cheers and celebratory gunfire from the men watching below.

Associated Press Photographer Joe Rosenthal snapped a now-famous photo of six marines struggling to hoist the Stars and Stripes atop the mountain, yet the flag raising was only a brief moment of triumph in what had become a bitter battle.

Marines would continue fighting for another month through hills and gullies with nicknames like the “Meat Grinder”, “Death Valley” and “Bloody Gorge”, suffering thousands of casualties for every mile of territory gained.

How U.S. Marines Won the Battle of Iwo Jima The U.S. Raised the Iwo Jima Flag, then Occupied the Islands for 23 Years

The U.S. Raised the Iwo Jima Flag, then Occupied the Islands for 23 Years

The U.S. occupation of the Ogasawara, or Bonin, Islands was anything but simple.

When six U.S. Marines raised a flag over Iwo Jima in February 1945, they were laying claim to the slopes of a mountain that was part of a strategically important chain of volcanic islands south of Tokyo. The Ogasawara Islands, also known as the Bonin Islands by Americans, were largely uninhabited. But during World War II, they offered a place where the invasion of Japan could be staged.

The islands themselves weren’t completely empty—they were home to thousands of Japanese people, many of them with British and American ancestry. And the American victory turned most of them into refugees when the United States occupied the islands for the next 23 years. The story of the Bonin Islands is one of a group of seemingly obscure islands caught in the crosshairs of international conflict—and the effects of war and occupation still reverberate decades after they were finally turned back over to Japan.

The group of islands came by their Japanese name, which means “empty of men”, honestly. Though they seem to have been at least briefly occupied by Stone Age humans at some point, they were uninhabited by the 1670s, when they were mapped and named by Japanese explorers. However, they were only developed 150 years later, when American and English settlers established a colony after being shipwrecked there. The small community soon became racially diverse when sailors from whaling ships, some of them black, settled on the islands.

In 1860, Japan finally decided to lay claim to the islands and went to investigate. They found a small but diverse group of residents that hailed from everywhere from the Netherlands to Hawaii. Once the Ogasawaras became Japanese territory in earnest in 1875, Japanese settlers joined their ranks.

This diverse group of settlers lived quietly in small villages on the islands in thatched-roof homes, supporting themselves by selling goods to passing ships, hunting and weaving baskets and living off of fish, seals and sea turtles. Though the islands were technically Japanese, they were off the radar for an empire that had other, more pressing territorial and political questions on its hands.

During World War II, the obscure islands were suddenly of strategic importance, and islanders were faced with the realization that their homes were about to become battlegrounds. On Iwo To, also known as Iwo Jima, the island’s 1,000 were evacuated to the mainland in July 1944 as the Japanese military began a military buildup on the islands.

Residents may have suspected that the island would be home to some of the war’s fiercest battles, but they could never have guessed that they’d never go home. In just 36 days in 1945, the Battle of Iwo Jima resulted in 26,000 American casualties and the deaths of nearly 7,000 U.S. Marines. Twenty thousand Japanese soldiers fought in the battle; only 1,000 or so survived.

Then, after the war, Japan surrendered possession of the Ogasawara Islands - called the Bonin Islands by Americans - to the United States. The U.S. Navy occupied the islands until 1952 and administered them until 1968. Rather than let the historical residents of Ogasawara return home, the Navy only allowed people who were descended from or married to descendants of the islands’ original settlers to stay. Europeans and Americans were welcomed back, but only a small number of Japanese people were allowed back on the islands.

Related: Pacific: The Lost Evidence

History.com / Wikipedia / Encyclopedia Britannica / National WWII Museum.org / NAVY.mil / Department Of Defense / USMC Museum / My Heritage / Military.com / Daily Mail